Why Agile Software Development Techniques Work: Improved Feedback Cycles

One of the great debates raging within the IT industry is whether or not agile software development techniques work. My experience, and the experience of thousands of others, is that they do. One of several reasons why agile techniques are so effective, in my opinion, is that they reduce the feedback cycle between the generation of an idea (perhaps a requirement or a design strategy) and the realization of that idea. This not only minimizes the risk of misunderstanding, it also reduces the cost of addressing any mistakes. In this article I explore this idea in detail.

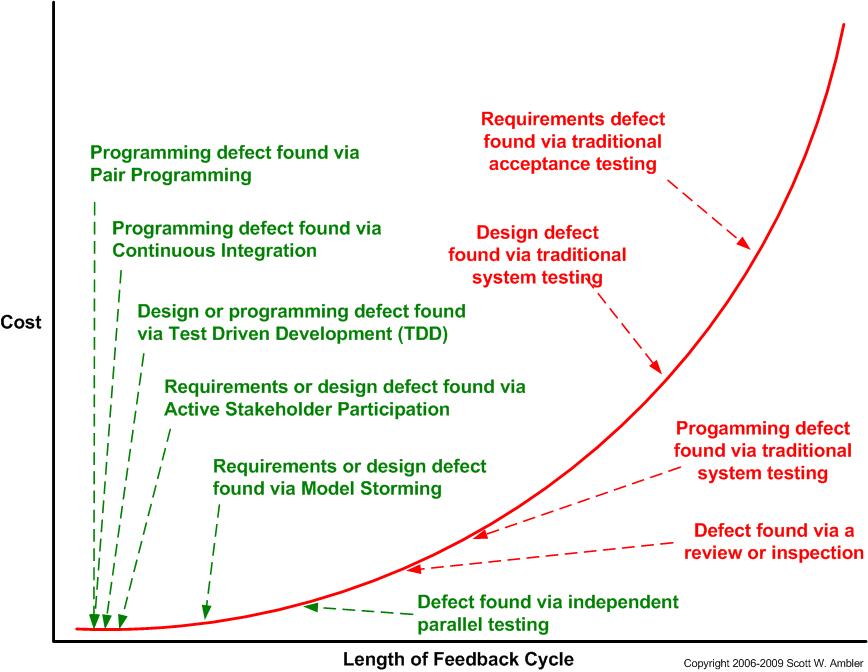

Figure 1 depicts the traditional cost of change curve, which shows that the longer it takes you to find a defect then on average the more expensive it is to address. The average cost rises exponentially the longer that you wait because you continue to build upon a shaky foundation, or as we’d say here in Canada, the problem snowballs. To be fair some defects become less expensive the longer it takes to find them, perhaps the defect is found in functionality that is no longer needed or perhaps the defect is now addressable by a reusable component that is inexpensive to deploy.

Figure 1. The cost of change curve.

In the past the X-axis of this curve was depicted in terms of the traditional project phases (requirements, analysis, architecture, design, …) but the real issue really is one of the length of the feedback cycle. Although the cost of change curve has been questioned since it was first proposed by Barry Boehm in Software Engineering Economics (Prentice Hall, 1981), Boehm had looked at overly bureaucratic environments (mostly US Government and contractors to them), the real issue seems to be around how steep the curve is. As an aside, modern development processes have abandoned the idea of phases in favor of an evolutionary (iterative and incremental) if not agile (evolutionary + highly collaborative) approach.

Figure 2 maps the feedback cycle of common development techniques (for the sake of brevity not all techniques are shown), summarized in Table 1, to the cost curve. Agile techniques, such as Test Driven Design (TDD), pair programming, and Agile Model Driven Development (AMDD) all have very short feedback cycles, often on the order of minutes or hours. Traditional techniques, such as reviews, inspections, and big requirements up front (BRUF) have feedback cycles on the order of weeks or months, making them riskier and expensive.

An interesting observation is that some people within the agile community believe that the agile cost of change curve is different from the traditional cost of change curve, arguing that the former is flat whereas the latter is exponential. My argument is that they’re the exact same curve, that because agile techniques focus on the virtuous, left-hand side of the curve that it appears flat.

Another interesting observation is that that many of the people who tell you that Agile doesn’t work confuse “code and fix” approaches with Agile approaches. This is likely because there isn’t accepted criteria for determining whether a team is agile, so it’s very difficult for them to distinguish accurately because they don’t know what they’re looking at.

Figure 2. Mapping common techniques to the cost of change curve.

Table 1. Common agile and traditional development techniques.

| Technique | Description | Feedback Period |

| Active Stakeholder Participation | Stakeholders (users, managers, support people, …) are actively involved with the modeling effort, using inclusive techniques to model storm on a just in time (JIT) basis. | Hours. A stakeholder will describe their requirement(s), then the developer spend several hours, or perhaps day or two, implementing them to produce working software which they can then show to the stakeholder(s). |

| Agile Model Driven Development (AMDD) | AMDD is the agile version of Model Driven Development (MDD). With an AMDD approach, at the start of an initiative you do some high-level, initial requirements envisioning and initial architecture envisioning. During development you model storm on a just in time basis. | Hours. With model storming, you explore a requirement with your stakeholder(s) or a technical issue with other developers and then spend several hours or days implementing working software. |

| Big Design Up Front (BDUF) | With a BDUF approach, a comprehensive design document is developed early in the lifecycle which is used to guide the implementation efforts. | Months. It is typically months, and sometimes years, before stakeholders are shown working software which implements the design. |

| Big Requirements Up Front (BRUF) | With a BRUF approach, a comprehensive requirements document is developed early in the lifecycle which is used to guide the design and implementation efforts. | Months. It is typically months, if not years, before stakeholders are shown working software which implements their requirements. |

| Code Inspections | A developer’s code is inspected by her peers to look for style issues, correctness, … | Days to Weeks. Many teams will schedule reviews every Friday afternoon where one person’s code is inspected, rotating throughout the team. It may be weeks, or even months, until someone looks at the code that you’ve written today. |

| Continuous Integration | The system is built/compiled/integrated on a regular basis, at least several times a day, and ideally whenever updated source code is checked into version control. Immediately after the system is built, which is often done in a separate “team integration sandbox” it is automatically tested. | Minutes. You make a change to your code, recompile, and see if it works. |

| Independent Parallel Testing | The development team may opt to deploy their system on a regular basis, at least once an iteration, to an independent test team working in parallel to the development team(s) that focuses on trying to discover where the system breaks. This is an agile testing strategy. | Days to weeks. Depends on how often the development team deploys their current working build into the test environment and how long it takes for the test team to get around to testing it (they are likely supporting several teams). |

| Model With Others | The modeling version of pair programming, you work with at least one other person when you’re modeling something. | Seconds. You’re discussing the model as you’re creating it, and people can instantly see a change to the model made by someone else. |

| Model/Documentation Reviews | A model, document, or other work product is reviewed by your peers. | Days to Weeks. A work product will be created, the review must be organized, materials distributed, … The implication is that it can be weeks, or even months, before the item is reviewed. |

| Pair Programming/Non-Solo Work | Two developers work together at a single workstation to implement code. | Seconds. You’re working together to develop the code, the second coder is watching exactly what the person with the keyboard is doing and can act on it immediately. |

| Test Driven Design (TDD) | With TDD, you iteratively write a single test then you write sufficient production code to fullfill that test. | Minutes. By implementing in small steps like this, you quickly see whether your production code fulfills the new test. |

| Traditional Acceptance and System Testing | Acceptance testing attempts to address the issue “does the system do what the stakeholders have specified”. System testing, including functional, load/stress, and integration testing, attempts to address the issue “does the system work”.With traditional testing the majority of testing occurs during the testing phase late in the lifecycle. Testers will write test cases, based on the requirements, in parallel with implementation. | Months. By waiting until the system is “ready for testing”, the testers won’t see the system until months after the requirements are finalized. |

Suggested Reading

This book, Choose Your WoW! A Disciplined Agile Approach to Optimizing Your Way of Working (WoW) – Second Edition, is an indispensable guide for agile coaches and practitioners. It overviews key aspects of the Disciplined Agile® (DA™) tool kit. Hundreds of organizations around the world have already benefited from DA, which is the only comprehensive tool kit available for guidance on building high-performance agile teams and optimizing your WoW. As a hybrid of the leading agile, lean, and traditional approaches, DA provides hundreds of strategies to help you make better decisions within your agile teams, balancing self-organization with the realities and constraints of your unique enterprise context.